Never Mind Fiat Currency: The Energy Economy

Renewable Energy, Fossil Fuels, Fission, Fusion, and Future Power

Power and the money, money and the power

Minute after minute, hour after hour

-Coolio

Any economist will tell you, when pressed, that money is just a value-store, a surrogate for actual wealth and power. It lets you hold on to value over time and spend that purchasing power later (or at least that’s the theory).

The actual wealth is typically the hard assets: land, minerals, capital improvements (machinery, tools, etc), food and textiles, and the like. And the power? Why, ever since the industrial age started, power is… power. Elecricity, coal, oil, jet fuel or liquid oxygen/liquid hydrogen rockets, steam engines powered by burning wood or splitting the atom - our power sources today nearly all come down to either direct electrical generation or one variety or another of fuel.

Marxists and similar class-warfare types will tell you that power is human labor. This is extremely arguably true for peasants laboring in the fields. But even there, everyone who has the choice would rather use an ox to pull the plow or use water to turn the mill. Concepts like the “lump of labor fallacy” - basically, that there’s only so much work to be done and it’s just a matter of how we divide it all up - discount at very least the skill of the person performing any sort of skilled work, and ultimately most work is skilled at least in its niche: you don’t want an inept cook, or carpenter, or electrician. Nearly only the interchangable “cog” labor is the sort you can automate with machinery. If you take the medieval society as your example: an untrained blacksmith can apply a great deal of effort and time but will not produce useful goods. But that is not our society and medieval recreation is a luxury hobby for SCA cosplayers these days, who would probably rather be Mandalorians or Tony Stark anyway.

Now there’s been a great deal of interest by the United States in having the world’s energy economy denominated in and transactioned in dollars; you have likely heard the term “petrodollars” applied to the economies of the oil-exporting states that mostly thrive on resource extraction and that term can be taken as simply “revenue generated from the export and sale of petroleum or petroleum byproducts”. You’re probably thinking of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, although the term applies to the rest of Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), also Russia, Qatar, and Norway. And of course the United States and Canada both do a lot of business in petroleum as well.

The world’s petroleum market is roughly $3 trillion annually as I write this at the start of 2025. That’s rather a lot of income. As my uncle liked to say, you could pay off my bar tab with that kind of money.

In the 1970s, soaring oil prices meant was a great deal of wealth accumulated by OPEC in the form of these petrodollars (and the term became somewhat mainstream), which led to some of the commonplace stereotypes you may know about wealthy sheiks; it also led to Adnan Khashoggi briefly becoming the wealthiest man in the world by being the arms dealer to the Saudi government. (This is not, strictly speaking, true - and acting as if it were is in fact one of the things that led to his downfall - but one must realize that when statistics of this sort are cited, they almost universally exclude the royalty of the various states involved as there’s the polite fiction that the vast wealth belongs to the nation. It was considered at best gauche to be living larger than the Saudi royal family or implying that one was wealthier, and when his benefactors decided that he was no longer in favor, his fortunes changed very quickly.)

For those of you who have ever wondered “why did the United States standard of living diverge in the 1970s and never recover” which is sometimes also asked as “why is there such a wage gap compared to what there used to be” - keep an eye on this, because it’s part of the overall answer; this is not the only reason the economy changed but it is frequently understated. I’ll come back to this later, when I talk about how to fix the economy and build the future we all want, but not in this essay.

But with that as the jumping-off point, the energy economy very much shifts in the 1970s due to tensions in the Middle East.

In 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack and invaded Israel in what's generally referred to as the Yom Kippur war. The Americans rushed arms to the Israelis, the Soviets to the Egyptians and Syrians, and things generally went poorly for the combined Arab forces. To support their other Arab brethren, OPEC cut oil production and decreed an embargo of oil sales to the U.S, Canada, the UK, Japan and the Netherlands, to punish the United States (and the West) for supporting Israel in the Yom-Kippur War; oil prices skyrocketed. Nixon made an attempt to push Project Independence (an attempt to shift the US to nuclear power); France and Sweden successfully made this transition but the US largely didn’t for various reasons (primarily: domestic availability of oil, and political opposition by the hippie-turned-environmentalist movement, who were of course Useful Idiots and catspaws for the KGB to sabotage America.)

Likewise, in 1979, the Iranian Revolution overthrew the Shah and installed the theocracy of Ayatollah Khomeini instead; this revolution and the subsequent war between Iran and Iraq disrupted oil supplies from the region. (And let’s not overlook: the Shah came to power in 1953, from a figurehead to suddenly an absolute monarch because the Iranian prime minister had nationalized the previously British oil production in the region - the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company - and the Americans and Brits put together the coup, which you’ll find under the name Project Ajax or Project Boot depending on the country… your CIA/MI6 tax dollars at work.)

Various attempts at alternative power largely weren’t cost-effective - the major exception being hydropower, which was rapidly developed and deployed more or less everywhere possible. Eventually, however, breakthroughs in photovoltaic solar and inexpensive large scale manufacturing (primarily based in China) brought down the cost of solar power generation to the point that electricity could be affordably generated during daylight hours in appropriate climates if land is cheap, and those three caveats are important. (Your other four major caveats are: storing power is hard - requiring batteries/flywheels/pumped storage; transmitting power over distance is inefficient and lossy; we often want power in the form of fuel rather than electricity though this is less important as there are plenty of things that would run directly on electricity; and last-but-not-least we may have an enormous lurking waste-and-replacement problem in the form of degrading photovoltaic cells or carbon-fiber windmill blades though this is probably a recycling problem.)

At this point, solar is efficient within certain constraints, wind is efficient in the correct environments, hydropower is efficient if your terrain permits it (and again if the local environmental movement doesn’t want to tear down your dams), and tidal power is … not terribly efficient, but it’s not really been deployed at scale, so you typically have prototype cost problems. Intriguing technologies like the ocean thermal energy converter (OTEC) seem plausible and work at prototype levels but haven’t been brought to commercial scale either.

And of course, there’s always controversy around nuclear power: conventional fission, thorium reactors, breeder reactors, pebble beds, fusion research, microreactors, fusion research and stellarators. Usually the concern there amounts to some combination of what do you do with the waste, or how do you prevent a catastrophe, and possibly some concern about how do you prevent nuclear weapons proliferation. (Perhaps not incidentally, that looks like it’s a concern back on the table: does Iran plan to nuclearize? Will Ukraine seek to regain nuclear weapons? If either of them does so, is Taiwan next, or South Korea, and if those two decide to can Japan be far behind? I think all of those are entirely plausible, even likely, given the current geopolitical climate, but I doubt my ability to forecast who’s next after that - as Tom Lehrer will tell you, however, the concern is not new… anyway, I’ve already written about that elsewhere on Substack so I’ll point you to that article, and not otherwise divert this one… someone else can run the betting pool on that particular topic.)

So with all the above as context, I started this article with a basic economics premise: currency is a ledger for interchange of actual wealth and power, and having said all the above, let me explain a bit further.

If we’re thinking of the baseline of the economy as wealth and power meaning “natural resources" and “energy” - and yes, I realize this is not strictly speaking the usual definitions, but hold with me for a couple paragraphs - then we have a relatively zero-sum game, by which is meant: there is basically only so much iron, copper, usable land, and other valuable assets to go around. (By comparison, perishable goods - typically crops - tend to be grown and spoil; their availability fluctuates - some times of the year it’s hard to find strawberries, for example, or would be without greenhouses or a global supply chain.) To use a particular example, there’s a certain amount more cobalt excavated, processed, and refined every year, but the total amount is static and the amount currently available is limited - and of course the relative demand for that asset versus the availability of it determines the cost, it’s the classic value equation. You can dig more mines - but not instantly, and of course it’s only found in certain areas.

Similarly, energy is relatively zero-sum - in most cases, if we are using energy to do something in one location it is not available to do another task elsewhere, and there’s only so many places you can put a dam on one river before it’s just a series of ponds (and thus, no longer a means of water-based navigation, transport, and certain types of productive fishing, even if you’re trading that off for water-based energy generation). Energy output increases relatively slowly and with the production of more power plants - and predominantly, by the consumption of more fossil fuels - which means that if you need your economy to grow quickly, you are going to tend to get the Sarah Palin solution.

But as even casual observation has shown - adding additional currency is easy, even at a “helicopter drop” level. All you’re doing is increasing the numbers in a ledger. If there are thousand currency tokens in circulation and suddenly the government injects another thousand, it doesn’t create new value - it just devalues the existing currency.

There is some level of energy arbitrage possible, of course, because energy generation with renewables has become remarkably inexpensive during certain conditions. Mostly, these are obvious: solar when the sun is high and the sky is clear, wind farms when the wind speeds are consistent but not too dramatically strong, hydro as long as there isn’t drought, and tidal power on the obvious tidal cycle. Of course, usage patterns for power do not necessarily map to convenient power generation cycles for these energy generation mechanisms, and the part that green power enthusiasts don’t like to talk about nearly as much is that you must also deal with the cost of a new set of energy storage infrastructure - and that hasn’t gotten better quite so effectively. You can’t store solar energy in large oil tanks (and synthetic fuel production, though it’s a lovely idea, is pretty inefficient today.)

Leading contenders for short power storage - or what’s sometime’s referred to as “time shifting” - are gravity based and battery based. The most popular gravity based mechanism is pumped storage - effectively, “refilling the dam” - which is sort of viable if you already have a dam and you’re treating it as a mechanical battery, but is pants-on-head levels of stupid if you’re in the middle of the Great Plains or the Sahara and you’re having to build a huge elevated reservoir of water to be a monster artificial lake just to basically … power a dam that you also have to build. Pumped storage is basically just using other renewables to backdoor your way into hydropower for “grid balancing” - being able to use hydropower to provide stable base load and then augment need for higher power demand with the renewables during the times of high power usage, which ironically makes the renewable power sources less valuable (since they mostly serve to keep the hydropower “water battery” topped off). There’s the ARES (Advanced Rail Energy Storage) system - which is basically “using trains up-and-down the side of a mountain as a form of gravity battery” - an interesting idea inasmuch as it can use existing rail lines and basically haul inexpensive mass as ballast to use electric locomotives as generators, then when power is cheap you pull the freight cars back up the mountain to be used for generation later when needed. Downside of course: you require a mountain (and a great deal of space) - quick video here for those interested. But at least you don’t need to flood a huge area.

Battery based storage is typically literal batteries - Tesla has deployed their Powerwall product at industrial scale calling it the Megapack; it’s in production in Canada, California, Alaska, Texas, and Australia, with lithium-ion batteries in larger arrays (and a newer battery technology in the coming Hawaii deployment). These package conventional batteries inside individual shells for mainenance, networking, power management, and cooling purposes. There are many other firms also deploying battery backup solutions of various sorts; one of the ones I thought more interesting if less conventionally recognizable as “batteries” is the set of development around vanadium flow batteries (or, closer to the labs, other redox flow batteries) - Sumitomo leads at this, and this technology has been slow to come to market, but these have some very real advantages for grid storage. They are easy to scale, they can remain charged for years without damage, they work in a wide range of temperatures, they have no noise or emissions, and because they will last a very long time compared to other batteries the amortized cost of energy storage is quite low. (However, vanadium is rare, heavy, relatively toxic, and this sort of battery is fairly bulky compared to lithium-ion batteries - which usually doesn’t matter so much, because this sort of power storage facility tends to be built on some relatively large swath of land.) There is also the slightly eccentric “battery” solution of flywheel energy storage - capable, proven, but generally only able to store a short time period worth of power (seconds or minutes) because the flywheel spins down rapidly when you start drawing power from it. Even a flywheel array tends to be regarded as more something to store up a lot of power and quickly discharge it all - like an enormous capacitor - so is used for things with very bursty power draws… for example, a particle accelerator or fusion plant or other high energy physics projects … or, oddly, roller coasters at amusement parks (see: Knott’s Berry Farm, Universal Islands of Adventure).

There’s also the concept of having “peaker plants” - for instance, natural gas plants that fire up only in instances of high demand - which leaves you building expensive generation facilities that run only a small percentage of the time, but which can start and stop at relatively short notice. (By comparison, coal generation or nuclear generation are not well suited to starting and stopping power production at short notice.) Of course, this means you are effectively building and maintaining a whole second power generation infrastructure as a “luxury tax” -to deal with power generation unreliability caused by weather and the mismatch between power demand and power generation cycles - and sooner or later someone will ask “why wouldn’t we just run the power generation systems that we can always rely on?” (The unsurprising answer is pollution - for the past couple decades we’ve called that pollution “carbon emissions” because Al Gore and Greta Thunberg achieved media capture, but it’s a more useful metric to to consider the broader spectrum of pollution. For heaven’s sake: handling carbon dioxide is easy, dioxins and heavy metals… significantly less so. But that’s why you don’t burn cheap bunker fuel in your local power plant.)

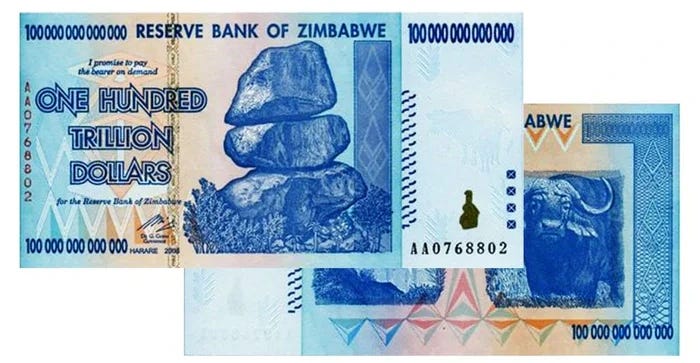

So - resources are finite and scale up with trade and resource-extraction/refinement; energy is finite and scales up with generation or resource-extraction but is generally faster to scale up than resource creation; and currency used to be a resource back when it was literal gold - or pegged to something - but after the Bretton Woods era, it is most frequently backed by the full faith and credit of the issuing country which tends to amount to Just Trust Us, Bro. But of course, countries have been known to undergo some pretty radical currency inflation, of which Zimbabwe was one of the better examples.

There was some truly spectacular hyperinflation in Zimbabwe in the early 2000s, which apparently peaked at something like 79.6 billion percent per month. I couldn’t make this up if I tried. Eventually they abandoned their currency and declared the US dollar their official currency (even this didn’t fix things: the bank ran out of US currency and the economy was poorly matched to the US dollar since most people lived on about $1.80 a day). So they went back to a Zimbabwean currency and - you’ll not be surprised to hear, this fell apart again.

So of course, the complaint about the petrodollar is that the United States is exporting its inflation - because the sale of petroleum is basically dollar-denominated; the dollar is the world’s reserve currency, and while OPEC sets the price of oil, the United States to an even greater extent sets the price of the dollar. The oil-rich nations predominantly feel like they’ve got a product in high demand, they can charge through the nose for it, and they do not like that the United States can to a certain extent devalue their enormous gains by clever financialization or outright Federal Reserve intervention. (Though: none of the heads of state are terribly eager to provoke a more direct kinetic response a la Project Ajax or another Gulf War, nor even Nixon’s Project Independence - which would, of course, have taken America entirely off foreign oil and eliminated our use of coal and natural gas plants as well - a no-carbon-emissions vision to warm or perhaps cool Al Gore’s heart.)

But if you wanted to have a currency that was deliberately not subject to hyperinflation - you would peg it to something. For those of you not familiar with what economists mean by that term, generally it’s a reference to having your currency exchange at a fixed rate with the currency of another nation - for instance, the Belize dollar is pegged to the US dollar such that you can “officially” exchange two Belize dollars for one US dollar. But it need not necessarily be literally another nation’s currency - because, more traditionally, paper currency was intended to represent precious metals (“hard money”) - silver or gold - which is why phrases like “the gold standard” or “the pound sterling” are part of the lexicon even though your ability to exchange paper currency for precious metals is not exactly a thing anymore. So, beyond that, you’ve got the various cryptocoin unit-of-work indicators which I will mention and not delve into in this essay; but also some economic systems have had currencies pegged to baskets of other currencies or multiple targets you could convert your currency into. If your immediate inclination is that this is about to be a huge hairball, you would be correct; a nation that does this typically as to have their central bank maintain a large foreign currency reserve with a variety of different currencies and conduct a certain amount of arbitrage between them in order to effectively balance the basket. Possibly the most famous example in modern history of this sort of thing blowing up is when George Soros successfully “broke the Bank of England” on Black Wednesday in 1992, shorting the pound beyond the ability of the British government to cover, and forcing them to devalue it - his Quantum hedge fund made a billion dollars in extremely short order, and this was back in the era when a billion dollars was really quite the achievement.

But the point was not to talk about everyone’s favorite boogeyman, but to talk about how to make a currency immune to that sort of thing. A currency that wasn’t free-floating, and that critically wasn’t pegged to someone else’s currency, but that was pegged to something tangible and under your control - is far more pragmatically backed than by your nation’s faith and credit, at least these days. If you were to have for instance a literal petrodollar - issued by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and pegged to a gallon of crude oil - that would be a hard currency. This will not happen - because that would lock the price of oil, and because other OPEC members would take it very poorly, and because market prices for goods in Saudi Arabia would be become very jittery as a derivative of oil prices even more directly than they are today - but consider it a hypothetical example.

But more to the point, if you wanted to define a stable currency for whatever purpose - perhaps to restructure the global economy, and … for instance, ensure that the dollar stayed solid while there was political instability in a lot of the rest of the world, you would need a solid economy and relative autarky in the United States (or, let’s assume for US plus allied nations, with some relatively close-knit definition thereof.) In order to do that, you need resource independence, energy independence: and a currency less susceptible to market manipulation. And if in fact you have energy independence and energy surplus - excess energy from solar, fission, fusion, OTEC, tidal, power satellites, or some combination of all of those and more - why, then you could peg your currency to perhaps ten kilowatt-hours of power. Hypothetically speaking, and don’t hold me to that number in particular. It would interfere with the ability to run the money printer, except inasmuch as we also run the power plants. But then again, people complain that Bitcoin already makes power plants into money printers, so perhaps that comparison is not so far afield anyway - and more to the point, whether or not cryptocoin computation prints money, it’s a fairly literal statement that AI computation does these days - so the calculations are probably best done for energy prices at the data centers. And whether or not power-to-cryptocurrency qualifies (arguably, this is worse than fiat currency) or power-to-productive-computation qualifies (arguably, it should, but a lot of LLM algorithms are slop), power-to-manufacturing almost certainly does in a reindustrialized America. And why, you could almost use that sort of stable currency as the backbone of a global economy in an uncertain world. Almost as if it had been planned that way.

We need you and @centaurwritesatyr to do some quick hit videos on this important work.

This has all that @centaurwritesatyr energy. Great article