Trolley Problems and the Kobayashi Maru

The fine art of taking the third option

Clang, clang, clang went the trolley

Ding, ding, ding went the bell

-Judy GarlandIf you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice

-Rush

You’ve likely seen this particular moral philosophy puzzle in one format or another, but in case you haven’t, it is a bit of a reductio ad absurdum between utilitarian and deontological ethics. The scenario setup is basically this:

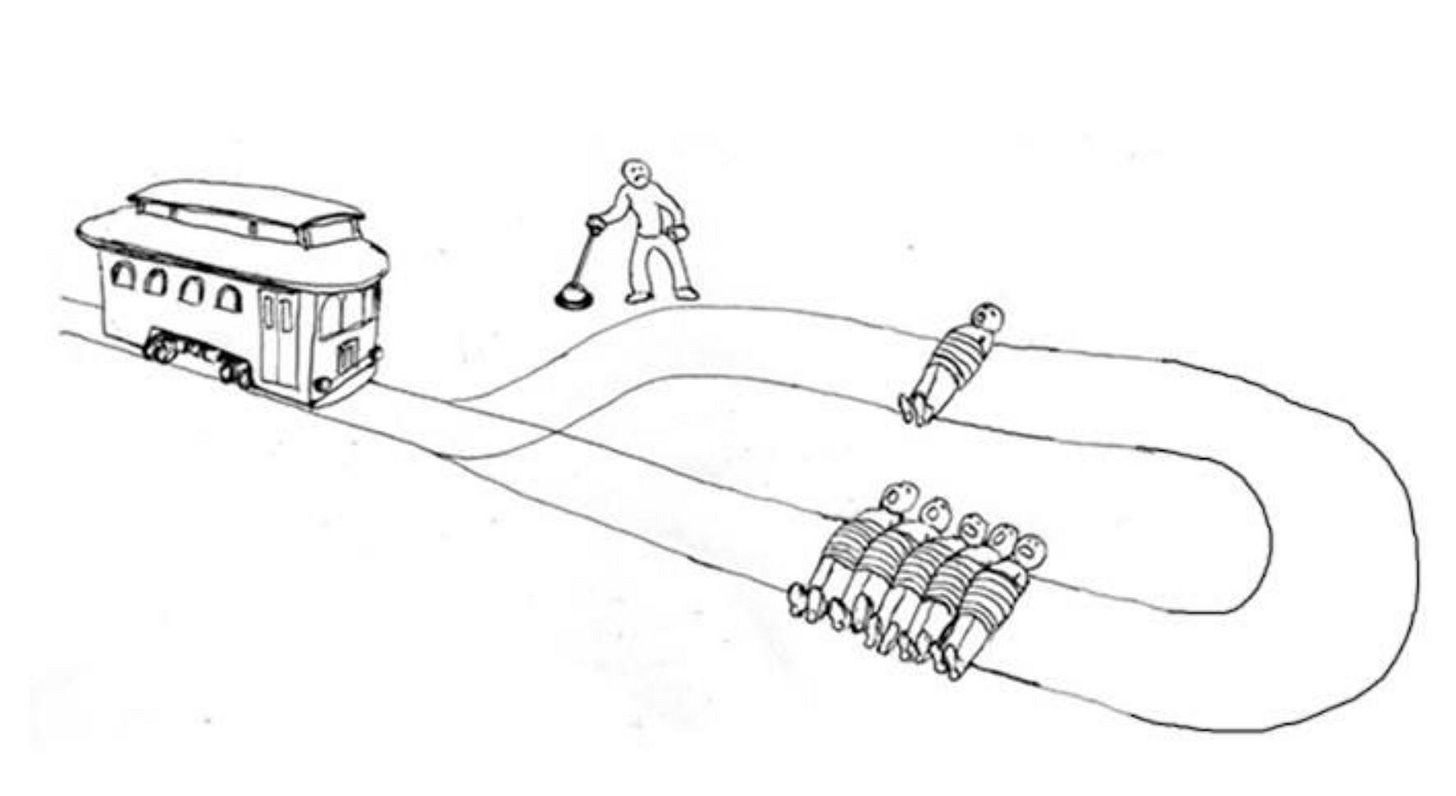

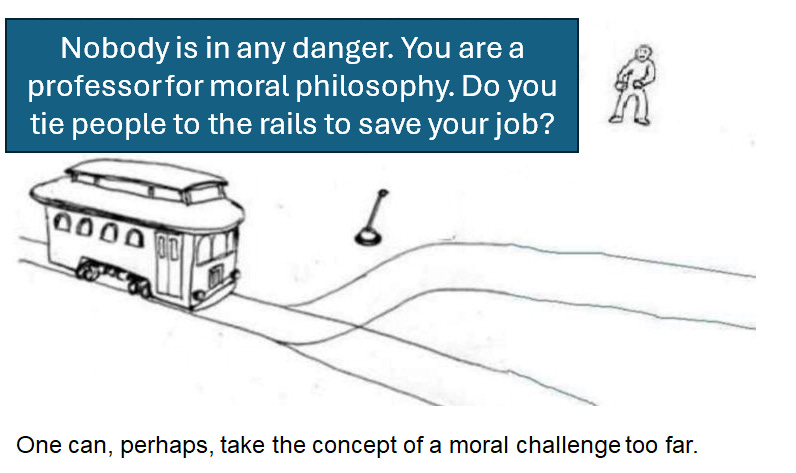

There is a trolley rolling down the tracks towards five people who are trapped on in its path. You have the option to leave the trolley on course - where it will surely squash them - or pull a convenient switch which will cause the trolley to change to another to another track where one person is standing, killing them instead but making you complict in their death instead of merely a shocked bystander. Then, the moral philosopher posing you this puzzle attempts to understand why you choose one option over the other, and perhaps introduces additional confounding factors as to why you might choose one path or another.

It usually comes with both a caveat that “There is no ‘answer’ – the Trolley Problem is a thought experiment, not reality, and cannot be (satisfactorily) solved” and also an equally irritating second question of “having figured out how you would answer the question, what would you REALLY do?” thus forcing people to confront whether their armchair morality actually matches their real world morality.

At the risk of speedrunning philosophy class, one might summarize as follows.

The deontological answer, which you are most likely to think of as being Immanuel Kant’s answer, is: don’t pull the lever, because you would be taking an immoral action (deliberately choosing to murder someone) in order that the other five would live.

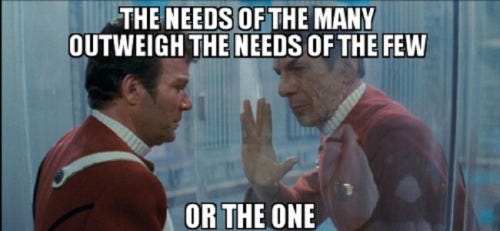

The utilitarian answer, for which we generally credit Jeremy Bentham (or you might also think of John Stuart Mill), would instead land on the consequentialist side of the table of “the greatest good for the greatest number” and decide that preserving five lives outweighs preserving one life, so would pull the lever, deliberately killing one person by their own actions but preserving five people.

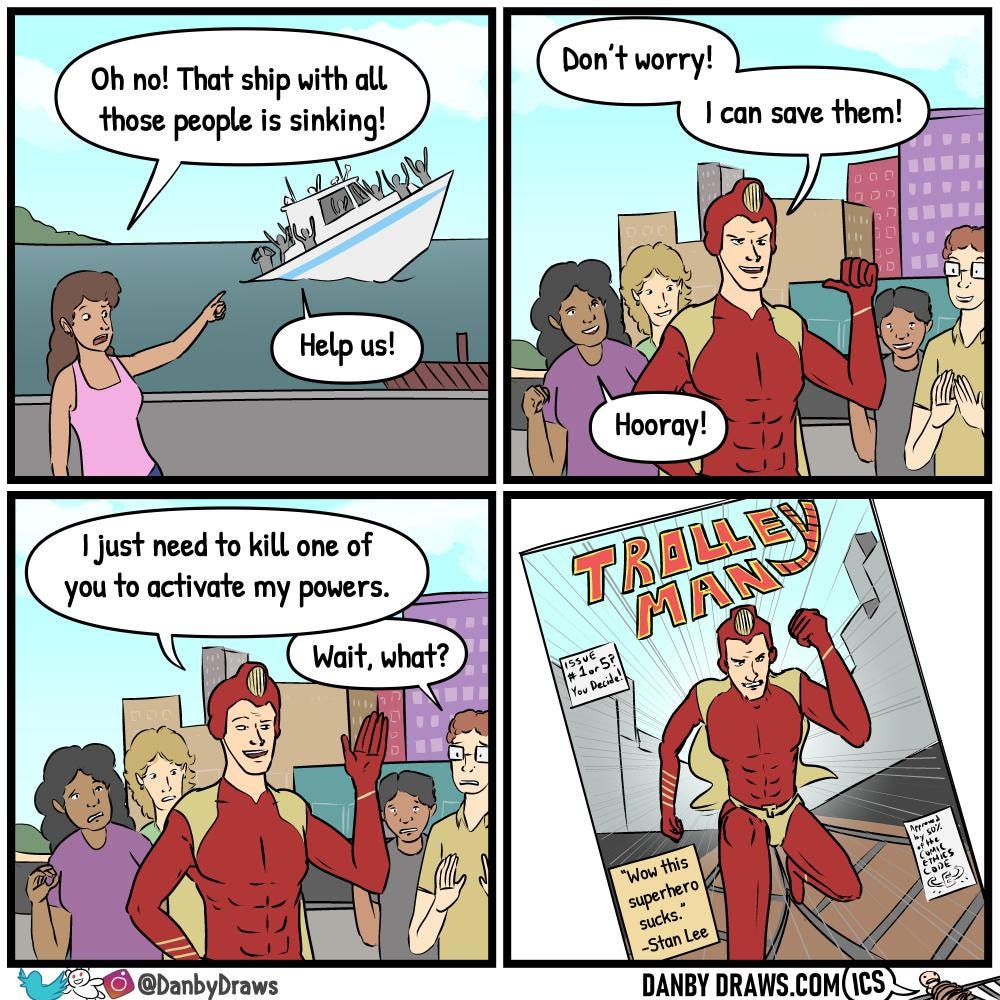

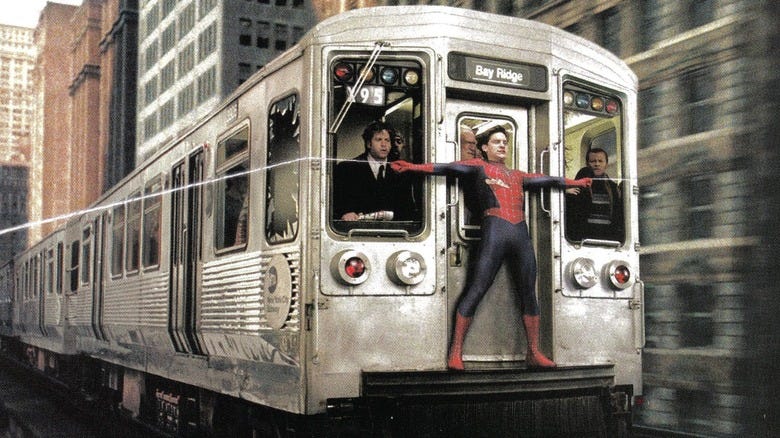

There are various odd variations on the trolley problem usually presented as followup once someone has declared their moral stance, with additional complicating factors: what if you know some of these people - for instance, what if the five people were particularly villainous, or already on death’s door? What if the one person was young and had a lot to live for, or was someone you particularly cared about like a friend or relative or loved one? What if you had to take a more active role, such as pushing someone onto the tracks to divert the trolley rather than just pulling a lever? This is sometimes presented as “The Transplant Problem”, where an amoral surgeon has the option to save five ailing patients by killing one healthy client who has come in for a checkup and transplanting their organs into the sickly patients, is the doctor correct to kill off the healthy patient in order to aid the others in need? Or the “Fat Man Problem” - would you push a fat man off a bridge in front of a trolley to stop it so that it would spare the five guys further down the path? (In this hypothetical example, you are apparently jacked enough to manhandle about someone who is both fat enough to stop a trolley, but you are not actually Spider-Man and can’t jump down and stop the trolley yourself.)

These last examples, incidentally, tend to reveal one of the classic problems with the simplicity of this moral philosophy example: they label psychopaths as utilitarians, which… hmmm. Maybe you have a point.

There are some fun simple variants on this puzzle, neatly automated for your clicking pleasure at the following site.

Generally, when you are given the Trolley Problem you aren’t permitted to Take A Third Choice (like derailing the trolley so as to crush no one) but often people like to try to theorize how to get out of this no-win scenario.

Or… there’s some alternate solutions proposed.

Usually along the lines of D&D players trying to optimize for maximizing their kill count (and thus, their experience point total).

For instance, it looked like this kid was going to find a Kobayashi Maru solution to the Trolley Problem, but instead he found the Good Place solution.

Perhaps I should explain the Kobayashi Maru solution, for those who haven’t encountered that bit of pop culture.

In Star Trek (in particular, in The Wrath of Khan), the Kobayashi Maru is a Starfleet training exercise that puts cadets in a no-win scenario. In this test, the purported goal of the exercise is to rescue the unarmed civilian ship Kobayashi Maru, which is damaged and stranded in the Neutral Zone territory between the Federation and the Klingon Empire. The cadet being evaluated must decide whether to attempt to rescue the Kobayashi Maru—endangering their ship and crew—or leave the Kobayashi Maru to certain destruction. If the cadet chooses to attempt a rescue, they will be assailed by a hostile Klingon force, appearing initially somewhat dangerous but quickly escalating to completely overwhelming.

But in practice, the purpose of the Kobayashi Maru training exam is not to win but to learn from losing (in a simulation) and make decisions accordingly, so as to test your character and understand your strengths and weaknesses. Also notably, no one has ever successfully completed this exam except for Star Trek’s famous captain James T. Kirk, who was the only cadet to rescue the Kobayashi Maru (on his third try) by hacking the simulation to make success possible.

The phrase "Kobayashi Maru" has entered the popular lexicon as a reference to a no-win scenario. The term is also sometimes used to invoke Kirk's decision to "change the conditions of the test” - it is a classic example of Taking A Third Option (rather than the two presented unpalatable options) and finding a better way, unconventional way out. Uncharitably, it’s just cheating; charitably, it’s figuring out how to win a no-win situation by changing the parameters… where that line gets drawn, of course, can be a matter of debate.

If you’ve seen The Wrath of Khan, you’ll note that it ends with a scenario where one of the participants must in fact make a Trolley Problem sort of choice.

But also, if you’ve seen that movie, you probably also know that though the movie ends there, the story does not in fact end there.

Maybe you can Take a Third Option after all. (After all, in the world we live in, it’s rarely as simple and binary a decision as a Trolley Problem, and it does not often have authroial fiat preventing you from finding a better path - but conversely there is no guarantee that you will have any such third option or that it will be viable, whereas audience outcry at the end of Wrath of Khan set the course for the next couple movies to see to it that there was a happy ending to a story that seemingly couldn’t have possibly had a happy ending.)

But it does make a delightfully metatextual statement on the morality play that Star Trek usually gives us that there was a correct answer to the moral enigma just as Kirk solved his Kobayashi Maru no-win scenario: by introducing a way to win that wasn’t in the system; an Out-of-Context Problem for the scenario designers; or as it’s more generally regarded: he cheated. (You will find that this will also usually be the complaint by moralists when you actually solve the problem but do so in a way that doesn’t suit them or doesn’t suit the constraints they want to place on it. When you find yourself being castigated for saving the day by not following The Rulebook, it is generally a good sign that what is in error is both the critic and the rulebook; one may find that all too often the Wisdom of Bureaucracy or the Wisdom of the Crowd is mostly just ossified knowledge of How It Used To Be or wishful thinking of the Road-to-Hell-Paved-With-Good-Intentions sort.)

Now, one might be forgiven for asking: why does any of this matter? Occasionally, one may ask this as regards any issue of moral philosophy, or perhaps even philosophy in general, as mostly this is an introspective art and high-minded edifices of moral superstructure often turn into a Gordian Knot of contradictory rules and a morass of exceptions.

But of course, if you are familiar with that metaphor, you undoubtedly know how Alexander solved the Gordian Knot.

We’ll explore this more in several essays to come, before we follow Alexander’s example and turn to more more practical matters. Subscribe and follow our journey.

this is amazing

nice article