Back on the Chain Gang

A modest proposal to restore law and order, deport illegal immigrants, and not disrupt the agricultural economy

You load 16 tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

St. Peter, don't you call me 'cause I can't go

I owe my soul to the company store

-Merle Travis

During the Great Depression, shantytowns - “Hoovervilles” - sprang up across America, living encampments of improvised shacks and tents and impromptu buildings for people who couldn’t afford anywhere to live. These makeshift settlements were built by squatters, disparagingly nicknamed after President Herbert Hoover who was widely blamed for the economic crisis, and therefore became a symbol of the suffering during that time period; these slums were essentially communities of makeshift shelters constructed from scrap materials like cardboard and wood, often headquartered near soup kitchens or other food sources for the indigent in cities where people could expect a handout.

Incidentally, it used to be the policy that not only were such things not permitted, but the police or fire department was deployed to burn down the Hoovervilles; Seattle’s Hooverville was built on a place known as Skid Road, a term still occasionally used to this day. But in general Hoovervilles became a commonplace problem because there was widespread leftist support for dispossessed squatters and a desire to blame the Republicans (personified/exemplified through Hoover) - they were only dealt with when public outcry became sufficiently overwhelming that otherwise sympathetic public officials were forced to act; the more things change the more they stay the same.

So today, tent cities are again common, but so is “public camping” - the 2018 case Martin v. Boise produced the somewhat unexpected ruling that vagrancy was a civil right.

Martin v. Boise was a 2018 case in which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that cities cannot enforce anti-camping ordinances if they don't have enough homeless shelter beds. The case was brought by six homeless plaintiffs against the city of Boise, Idaho. The court ruled that the government cannot punish people for sitting, lying down, or sleeping outside when they have no other option; also, if someone is asked to leave public space, they have the right to ask where they can go where shelter will be provided for them. (In 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Martin v. Boise.)

As you might expect, public parks and other land were claimed as living space by vagrants, who were quite happy to live close to the sources of free food, free bus passes, social services, needle exchanges, and in many cases easy access to areas with pawn shops and lack of enforced laws about shoplifting and petty crime.

Perhaps this will change to an extent with the Supreme Court overturning Martin v. Boise, but likely there will need to be not just a homeless sweeps or incarceration program but also some level of Public Works Administration reemployment program to move people back into productive life (as well as broad mental health and drug treatment programs and a re-employment-to-housing pipeline to reintroduce our more feral homeless citizens into productive society in a fashion that doesn’t immediately turn predatory). I would hope for some sanity along the lines of the successful programs from faith-based organizations being permitted, but that seems to have become relatively anathema ever since the New Deal did its best to centralize state loyalty above charity or religious aid.

Now this is not intended as a primary fix for homelessness - indeed, this is a much larger problem and despite looking relatively monolithic, there are a variety of different problems that are conflated together into the generic category of “homelessness” - and because there are several root causes that need to be addressed and several fixes that need to be applied, I’m going to write about this separately. But it is clear that our current homeless-industrial complex of various NGOs that exist to grift off the system and perpetuate the problem does not work: they are enablers rather than curing the situation.

Yet, with that in mind: one component of the solution is indeed to provide a productive New Public Works Administration Program - both to fill the role of America’s agricultural workers, and to build necessary infrastructure (housing, et al) to support that population - work camps, in more affordable regions where the labor is needed, rather than buying-and-repurposing hotels in high-priced cities. And to the extent that these new work camp areas require additional build-out of other support infrastructure - utilities, police and fire services, kitchens, health clinics, and the like - all to the good; these can be built with capacity to spare to serve the local communities as well in order to make them a net positive to the region in a way that an influx of homeless might otherwise not.

But the estimated number of undocumented immigrants in the United States is around 11 million, and estimates for the potentially employable homeless are more in the 750,000 to 1.5 million range depending on which groups you poll. Though it’s a worthy cause to return these people to productive employment, this would seem like it isn’t going to suffice. (Not to bury the lede: it very well might - not nearly all of the illegal immigrants in the United States are farm workers - but for those who aren’t, many of them are also gainfully employed doing other jobs that we’d still need done - think of all the Latino workers you see waiting to be hired at your local Home Depot, doing daywork construction or roofing or other light industrial jobs. So let’s carry on with this thought on the employment prospects for Americans; we want a productive America.)

There’s some prospect that you might get some portion of the chronically underemployed to return to work in a New Public Works Administration Program, and that number is not small - best estimate is that there’s 21 million American men who are of working age but not employed and not seeking work, who for various politically motivated reasons the government doesn’t want to count as unemployed. Some are disabled, some are unpaid caretakers, some are - as you’d expect - in jail, some are depressed and have just given up seeking a job and have stopped being counted by the economists, some are just idle for whatever reason and the reasons are legion. One can’t count on any reasonable fraction of these people to want to suddenly return to work. But a few percent will be enticed back. Not all that many by farm work, but perhaps as America re-industrializes and infrastructure projects come back into vogue, some of the trades will be increasingly attractive. We’ll count on no more than 2% of those, and round it to 400,000 people, but our envisioned New Public Works Administration Program is likely to see a lot more in all its various roles if that gets some mileage; back-of-the-napkin estimates range from 3.4 to 4.6 million workers willing to rejoin the workforce on a full time basis and slightly more than that willing to do so on a part time basis - as many as six million. These are likely to be older workers, so perhaps more skilled but also perhaps capable of less hours or requiring other accommodation. But if and as America properly reindustrializes - and especially if this is microindustry, local to these workers and suited to their capabilities and offering worthwhile compensation, we may find a significant labor pool for onshoring industry or constructing certain categories of infrastructure.

But as you can tell from the forecast - the core fraction that you are likely to get from a New Public Works Administration Program for agricultural labor is low. So, let’s talk about the carceral labor pool.

As of the end of 2023, the United States had around 1.8 million people in prison, and a great number of those are either currently engaged in prison labor, not readily suited to work-release, subject to sentences that don’t permit this kind of role (e.g. solitary confinement), or are just not the sort of people who are going to be capable of doing this kind of work without extraordinary supervision.

So clearly there isn't enough prison labor currently. But there's typically a million prosecuted felonies a year, another 780,000 unprosecuted felonies per year,

But that's mostly because the criminal justice system has stepped well back from the days of effective incarceration. A great number are not prosecuted, or are plea-bargained to some immediate release.

In 2023 in the US there were reported 6.41 million property crime offenses and 1.22 million cases of violent crime. Typical reporting rate would indicate that actual crime rates were roughly a third again larger than this number. And of course, widespread decriminalization of marijuana has apparently caused reduced crime statistics as many states have simply legalized what they would previously have arrested their citizens for; when this produced an uptick in small scale larceny and theft, California reclassified minor thefts so as to conceal the effects of the ensuing crime wave that widespread drug use and tolerance for criminal behavior was causing.

It would require considerable effort on the court system (or expedited option for plea-bargaining) as well as a change in policy and a good bit more law enforcement pressure to apprehend and detain criminals, but you could reasonably forecast an additional convict labor workforce of 2.1 million short term labor (gross misdemeanor and minor felony) as well as a longer term accumulation of roughly 600,000 longer-term laborers (felons with longer sentences assigned primarily to labor roles) annually if the objective was to retain a worker pool; these are forecast to stabilize at roughly 8 million in the long term (2 million short-term revolving in and out, 6 million under longer sentences). In addition to the New Public Works Adminstration program, we’d be at about 9.5 million people. Which would imply that we’d have to put most of the existing prison population to work also, and that seems unlikely - many of them are already doing prison labor, others aren’t eligible for work release because they’re too dangerous.

Wait a minute - is that actually plausible? Well, in any government, the enforcement of certain laws can be influenced by political motivations: in recent years in the United States you’re likely to have seen this particularly in areas like shoplifting and theft, or what is or isn’t considered offensive or protected or “hate” speech, or whether the investigation of a crime would support social justice - or obviously immigration enforcement.

Some cities and states have adopted "sanctuary" policies that limit cooperation between local law enforcement and federal immigration authorities. These policies can prevent local agencies from using resources to investigate, detain, or arrest individuals based solely on their immigration status. This selective enforcement can be seen as politically motivated, especially in regions where there is significant support for immigrant communities. For example, California's Senate Bill 54 (SB 54), known as the California Values Act, restricts local law enforcement cooperation with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which - to say the least - has been a point of contention.

Sanctuary cities are an example of selective enforcement. There are instances where federal immigration laws might not be enforced rigorously in certain jurisdictions due to political beliefs or to avoid alienating specific voter bases. This can manifest in less aggressive actions against undocumented immigrants for minor offenses or in the prioritization of certain cases over others.

In some jurisdictions, prosecutors might decide not to pursue charges for shoplifting below a certain monetary threshold, often citing overcrowded courts or the belief that these are minor crimes not worth the resources. This has been particularly noted in discussions around policies like those in California where Proposition 47 redefined certain thefts below $950 as misdemeanors rather than felonies, leading to criticisms that it has contributed to an increase in shoplifting. Or you might find the police choosing to park patrol cars in polite suburban neighborhoods and write speeding tickets because the ticketed drivers actually pay the tickets and there’s much less risk of bodily harm than the same officers performing enforcement duties in more hazardous neighborhoods. Also, the local donut shops are better. But this of course leads to the police not actually reducing dangerous crime - just basically acting as tax collectors from well-behaved citizens who can be lucratively fined for extra revenue.

There's an ongoing trend where some observe that laws are not enforced due to political ideologies that view certain crimes as outcomes of societal or economic conditions rather than individual moral failings. This perspective - “social justice” - can lead to less stringent enforcement, particularly in areas with progressive leadership, aiming to address root causes with incentive structures rather than addressing criminal behavior through punitive measures.

The political motivation behind not enforcing laws can also stem from legislative actions that alter the classification or penalties of crimes, thus indirectly affecting enforcement. When laws are changed or reinterpreted, enforcement practices follow suit, reflecting the political climate or voter sentiment in that area. This can be as-directed, or it can be knock-on effects; unintended consequences are common.

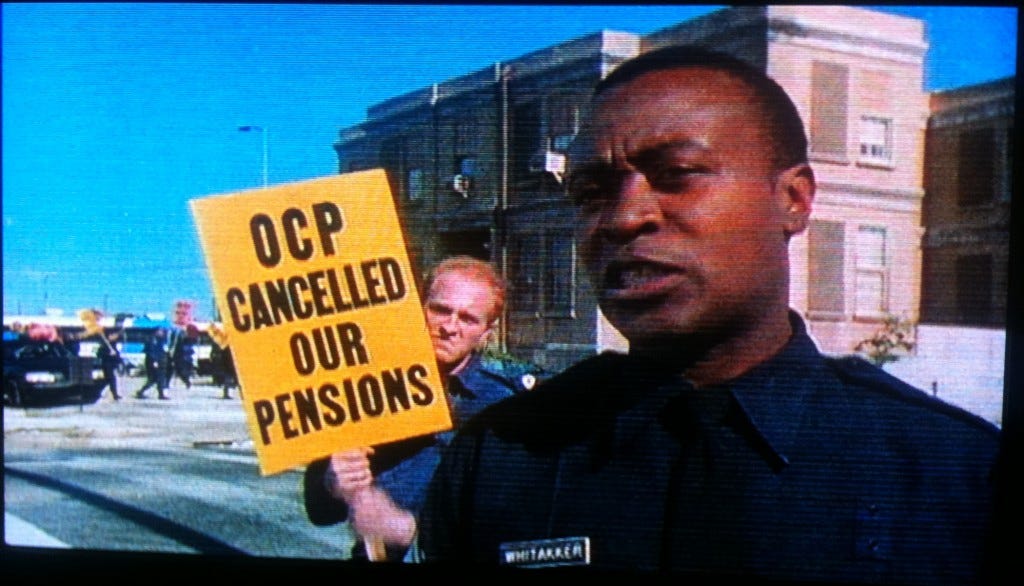

The enforcement of laws can also be swayed by public opinion, media perception, and political pressure, especially when high-profile cases or movements (like those advocating for criminal justice reform or immigrant rights) gain traction. Politicians might respond to this pressure by directing law enforcement to prioritize certain issues over others or to adopt a more lenient approach to enforcement. This can also produce blowback effects when “defund the police” produces bare-minimum-compliance law enforcement and scenes out of Robocop.

Some laws might face legal challenges or judicial blocks, like the case of Texas' "sanctuary cities" law, where enforcement was partially halted by federal court rulings, reflecting a judicial check on politically motivated legislation.

All that being said… would it be possible? Yes. But it would take some time; there is definitely some build-up necessary to make this work.

This would be an enormous expansion of UNICOR (Federal Prison Industries Inc) as compared to what they do today. Picking crops is relatively low-skill labor as compared to the manufacturing work that UNICOR typically makes today, but it does still require penal guard staff and the proximity of a local prison facility to be bussed to and from on a daily basis for work shifts.

Today UNICOR makes a variety of products and services, including:

Clothing and textiles: Military clothing, household items, gloves, draperies, bedding, and more

Electronics: Electronics and components

Furniture: Office furniture, accessories, and more

Metals: Metals and wire

Refrigeration equipment: Refrigeration plants, packaged refrigeration units, and more

Vehicle repair and remanufacturing: Vehicle upfits, remanufacturing, and fleet services for the military and federal government

Services: Graphic design, printing, call centers, help desks, and distributing warehouse operations

Energy conservation: Energy conservation products and services

Yes, if you're in the military, odds are your uniform (though probably not your armor) was made by incarcerated labor. And somewhat ironically, if you’re in law enforcement, your badge may be made by convicts.

There may be an immediate objection to the effect that this is basically slave labor. This is, however, the exemption allowed in the 13th amendment.

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

All right, so it's legal: that's still not enough people today. Correct, if we need to replace the full number being deported. But neither are we likely to remove millions of illegal immigrants in the next few months. And you may note that there’s a prominent “if” in that assertion - because not nearly all those migrants are farm workers.

(And one might point out that you could, at least in theory, sentence the illegal immigrants to hard labor and then deport them upon the completion of their sentence. You're unlikely to get very productive workers, though, compared to migrants who are looking to generate remittances to send back to their families: capitalism is a much more effective motivator. I present that option mostly to discount it, rather than to advocate it.)

So if we’re of the impression that we actually need the eleven million or so illegal immigrants that we currently have, and that most of them are agricultural workers - then we may still have a path forward, albeit a choppy one. Now incidentally, that’s a pretty dubious assertion, there’s reason to think that there are some significant census difficulties here and that in fact what we have may be misreported, but likely not dramatically misreported if only because logistical issues make it difficult to obscure literal millions of people. So for the moment - let’s work with these numbers as at least in the right ballpark.

But hold up. Of those eleven million illegal immigrants today, how many of those are actually agricultural workers? It turns out that the estimate is actually something more in the neighborhood of 280,000 to 450,000, depending on who is doing the estimating. All this hullaballoo about “who will pick your crops if we deport them” is mostly a mirage and a distraction by the same people who wanted open borders in the first place. If you instead asked “but who will sell your kids fentanyl if we deport the illegal immigrants” you might find significantly less enthusiasm for keeping them.

Usually some myopic sort will at this point cite a statistic saying that illegal immigrants are more law abiding than the average citizen population: you can tell, you see, because the rate at which they are caught and successfully prosecuted of felony crimes and convicted is a lower per capita rate than the average US population. Of course, by definition, literally every illegal immigrant is a criminal, so that statistic is obviously actually 100%.

And if the well-meaning liberal then insists “no, immigrants commit less violent crimes per capita” - well, then first correct them.

And then ask them who is committing all the violent crimes per capita in the US today. It’s always a fun conversation. Or for that matter, who is committing all the violent crimes per capita in Europe today.

Once you are done watching your interlocutor’s head explode, though, we should actually return to the question: what are the rest of the illegal immigrants doing, if not working the fields?

And you probably already know, if you’ve ever gone by Lowes, Home Depot, or any other big box construction store and noticed that you can not only buy supplies there but hire a few laborers who will hop in the back of your pickup truck and ride to the job site. Or if you’ve had your roof repaired and noticed that the workers have their jukebox tuned to the local Latin radio station. A lot of construction runs on cheap labor, subcontracted from local businessmen. If you wanted to put the squeeze on illegal immigration, you could readily start here - but it would also worsen the housing market, and potentially fine or jail a lot of entrepreneurial American construction company owners. (And a “hire American” program that comes with a reprieve for having employed illegal immigrants is probably going to be some sort of de facto compromise; certainly labor costs are going to go up, but on the upside, that money is going to reinvest in American workers rather than be sent south of the border as remittances.)

Beyond these obvious categories? You could still answer by stereotypes and you’d be significantly correct. Food service (either literally cooking, or delivering your Doordash), janitorial and hospitality (including maids and housekeepers), transportation (who drives your Uber? the same guy who delivers your Doordash), and (typically light) manufacturing/textiles. If you expected me to say “crime” - you might be surprised - less than you might think, because as a rule these guys do not want to draw the attention of law enforcement, it falls harder on them than your average gringo.

It’s probably harder to reliably push that over into convict labor - though not necessarily impossible, if part of a retraining program - but is more likely to suit the New Public Works Adminstration model and a renewed focus on re-employing Americans in the trades. And of that aforementioned 21 million Americans who have fallen out of the work force - these people might very well come back into the trades… at least on a part time basis, if that’s an option.

This will have the benefits of improving our nation’s economic welfare, reducing unemployment, reducing homelessness, retraining and reskilling workers, rebuilding American industry, and eliminating dependencies on illegal immigrants for key job functions.

This is not an unmitigated good. It should be expected that labor costs will generally rise in the near term; even carceral labor is not likely cheaper than migrant labor, and correspondingly, the price of fresh groceries is likely to be somewhat higher. (Estimates vary; 7-15% cost increase for fresh vegetables and fruits is likely based on the mixed carceral and subsidized-NPWA staff.)

America has a significant work force available today. Mobilizing it will require some effort, and most parts of it will cost more than migrant labor. In the near term, Americans should use the H2A migrant labor visa program for temporary additional labor as it was created and intended for (and enforce its usage to keep those instances delimited as temporary from becoming permanent without following proper channels), augment workforce with carceral labor and with a New Public Works Administration Program to put American workers back to work, bring our infrastructure and industrial base up to par to compensate for decades of neglect and offshoring, and proceed with border enforcement and deportation as necessary to ensure the security of the nation. And maybe they’ll even build a wall, if we can’t come to a better agreement with our neighbors.

"But who will help me buy the fentanyl?" said the Little Red Them.